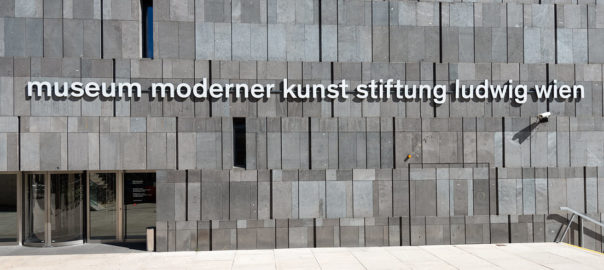

If you find yourself in Vienna, in a square of museums, you might be confronted with a stark grey building.

The building has high sided walls recall a birdhouse, a nest of interlocking features all clicking together. A thousand color-bled LEGOs made of Earth. Timeless building blocks that are at once filled with possibility and yet, largely featureless. This is Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, whose full name is a heaping mouthful, is also known as the Mumok and it is an unassuming and stately building with cut aways and soft corners. Dark and grey as the sky turned winter. This is its second location, its rebirth where it was entombed in basalt lava bricks after the turn of the century. The rough exterior gives away no hint that inside the walls are lacquer white – futuristic and soft. Modern and easy as any other art museum of this age.

A poster over the ticket booth reads:

Der Prater ist geschlossen. Kommen Sie ins Museum!

“The Prater [a nearby park] is closed. Come to the museum!”

A gift shop sits behind the ticket counter, a cafe looming over the space and white hallways, grey staircases, and black clad attendants lining every gap.

During renovation only the lower levels, all four of them, are open. The building yawns in all directions, carving into the Earth, climbing up to the sky.

But on our trip, we descend.

The first floor is small. A walkway, more like a cat walk, contains a large strange sculpture that looks at home in any science fiction of the 1960s [though its inception was in the late 20s]. The plaque says it is an “Endless House” which I immediately doubt. The idea is that a house should conform to any space that people have need of. The modern house is built on structures created based on our building blocks that we adapt and conform to, but this house with its slopes and wild openness, invites a space to be anything we have need of. It adapts to us instead. It questions how we make and relate to the spaces around us, invites even the room we’re in to suddenly come under attack from the thought that it isn’t made for us but instead, made merely by us. Looking at each picture of the so-called “biomorphic design” is like looking into a surrealist painting one could live in. Instead of a dreamscape, it is a lifescape. A place anyone could easily insert themselves in. The practical possibility is not as applicable as the nature of questioning space itself. Which like all things, should be questioned before it is valued or acted on.

On the second floor, art is difficult. Even the word invites questions and confusion. Is everything art? Is art everything? Can art be deliberate? Can art be an accident? How does one curate art? How does one decide what is meaningful? Seems small to think that we can. Seems presumptuous to pick and choose winners but this is what we have from people whose lives have been more focused on these ideas than mine and who I have placed my trust in which is why when confronted with the second floor: a series of fairly mundane looking black and white pictures, I wonder if this is “art”.

Over the door is the name of the exhibit which I struggle with, “es kann sein dass man uns nicht töten wird und uns erlauben wird zu leben”. I walk along the poster board of images. Like all art I look at each picture and try to discern why someone would have chosen this one. A room of this ones. All the pictures are in black and white and every picture is industrial. Is this a mine? An empty room? A table? A sky? My blood runs cold without explanation. Images of broken metal, large fences, mine shafts, tall walls. Physical debris lines the room also. The wall, the fence, the train track, all sitting and rotting against the wall matching images with distressing tangibility. In each picture I see the idea of forgetting – I don’t know what I’m looking at until I’m told, but I also see the idea of remembering, of recording. An itch running under my fingers.

There are pictures of train tracks with vegetation growing between them, left unsupervised. Without context these pictures could resemble any walk I’ve taken in any number of abandoned places. Left unnamed these pictures are harmless, empty frames of a man bored and curious but instead they are collected here. Instead they were brought to a museum and displayed. Instead, at the end of the exhibit there is an explanation that I no longer need. Halfway through the images something had clicked inside of me and I figured out what I was looking at. No longer just a man’s meandering snaps but a documentary. No longer a simple mine shift but a tomb, no longer a wooden table but a torture device, no longer a room but a hollow place where only death came. “It is possible that they won’t kill us and they might allow us to live.”

There is no train of industry on the tracks grown over and no tools of progress made from the wrench on the floor.

The artist, Heimrad Bäcker, was once a youth in Austria who joined the Nazi Party but too sick to actually enact any horrors and separated by illness from the party he ended up questioning the ideals and effects of that very party after the end of the World War II. He spent the rest of his life collecting statements chronicling the Holocaust and the „nationalsozialistischen Tötungsmaschinerie“ [Nazi death machine] visually and through interviews. The pictures and rubbish lining the room are the finding of a man who could not turn away from what he witnessed. Instead leading to a life of documentation, questioning, and curation.

Before exiting the room is a roll of film, taken when the artist was a young teen. It is his first roll of film documenting a fairly common field trip to one of these camps. The images are amateurish, off-center, and largely show a boy enjoying a day trip with his classmates. The fact that they are taken in a place that would become ghoulish is juxtaposed with the carefree nature of the images. They are startlingly banal. I found myself holding my breath while viewing them, as if somehow they were a film, a movie that would unwittingly continue until it ramped up horrors but instead they stayed still. Just photographs. Frozen in a “before” and at odds with a room of “after”. The horrors were contained only in the invisible time between the two sets of images. In our shared history, in my mind, and in the ground under our feet.

I didn’t know it but I’d been holding my breath the entire stairway down to the negative third floor. My back tense, my lungs stiff, my nerves pulsing in terror as to what may lay even deeper in the belly of this building. Instead I hear the unmistakable friction of laughter. Entering the room with Alfred Schmeller’s “Giant Billiard” is exactly as you think it would be. The piece, a large, nearly room sized blow up boxing ring filled with three human sized white inflated balls. All of it filled with air, looking soft and pillow-like. The ring lined with rubber rope feels safe and gentle, cradling its contents. And then, as if it were only a light, a laugh breaks from between my lips too.

There are people stationed next to the blown up exhibit, their hands held behind their backs listening carefully to instructions from a bald man whose smile is hardly concealed. He helps them up, one by one, via a small ladder into the pillow pit and then waits. Like newborns they walk, swaying to and fro on a ground with too much give and then, in shock, one man falls down and in his place joy bursts forth from everyone. It is a well, unending. It is one minute of running and bouncing and testing. It is two minutes of purposeful falling and getting back up again. It is five minutes of knocking the large, soft spheres inside the exhibit into each other, letting gravity and motion turn humans into bowling pins. I watch them from the corner of my eye as I round the room, reading praise and explanations of this exhibit.

Schmeller wanted people to interact with his art I read as a couple holds hands and falls down into a pocket of the art. Schmeller wanted children to understand the power of art as a father and young son roll the blow up ball over each others bodies while they try and sink into the ground. And all the time, laughter. Every person who enters the room has the same reaction: a moment of stunned silence and then, gob smacked joy. Some people run over to the entrance area right away and some carefully skirt the edge of the room, starring back over their shoulder while others play.

And they don’t just play one way. People don’t enter the space and await instruction. They climb on and test. Each person a scientist in a brave new world. Feet pressing at the edges, hands gripping at the bands, pushing the balls, finding new ways to interact with themselves and with each other. And strangers! Even strangers are allowed to play together, rolling and testing and laughing along. A man outside the exhibit tries to take a picture and another rolls the ball to pretend to block him, sticking his tongue out in jest. This is humanity, I think while starring at the ballet in front of me.

This is art. A piece of art. In a very serious museum. The floor above me containing some of the worst atrocities humans have fit to print. And yet here, just one floor down, seems most human to me. Involuntary joy and the work of play. Each new person climbing into the art has to learn and discover it. Has to test it. Bounces and shakes and walks uncertainly and learns its beauty and its pitfalls. And plays.

The piece looks like a child’s toy. Not far off from today’s trampoline worlds and jungle gyms and yet, full grown adults bask in it. Allowed in this space, in the beauty and simplicity of art, to be allowed again to explore and play. As we were always supposed to do. Not making people into children again, but instead, unleashing us as adults. Allowing us to become art. To become play.

If Schmeller, the creator of Giant Billiards and former curator of mumok, was worried that children wouldn’t engage in art because it was simply walking around having conversations while starring at images, I feel like the final and fourth floor both confirms and refutes that notion. The floor is filled with artists who fall under the label of Chicago Imagists, a kind of broad surrealist post-WWII movement wrapped up in questioning social norms and jazzy loose painting styles that show humor and humanity more than careful precision.

The thing is that these pictures are transgressive but also mired to their place in time and therefore some of the subjects and ideas that they purport have become less taboo or even normalized over time. Starring at many of the images I find them to be, on some level, quaint. Spacey, colorful, bold, and bright but in a way more like the hazy acid trip of any modern movie than a real confrontation or provocation.

That isn’t to say that the pieces weren’t good but that placing them all together felt like a way to travel back in time and visualize what must have been difficult then. What must have felt like a mountain to climb, or a cause to fight is now more like a gentle slope or a whisper to me. Many of the pictures played with the idea of women’s role or confusion over a sense of self that seemed in line with modern thinking. Some of the pieces played with gender and self presentation. Dysphoria or distortion of the body through alteration felt at once extreme for its time but also on the cutting edge of modern debate. Bold lines and bright colors lit up bedrooms and bodies and cartoonish figures all mocking the viewer. Daring them to ask what the nature of the images was supposed to be. At times, it felt more like inside jokes than art.

My favorites pieces looked like a mix between comics and surrealism. Thick lines around primary colors in easy to digest shapes with barely any texture to suggest meaning. A self portrait where the only identifiable shape are feet, the rest a washed out texture of soft colors and strange meandering lines. An image of a woman whose body is ripped apart by texture and whose shape is spaced incoherently along the canvas. A machine called the de-colorizor, with two bubbling jugs of clear water and no sign explaining what, exactly, is being de-colorized.

I enjoyed this collection for its unbridled playfulness and its sense of “self.” Since the artists all belonged to similar collectives you could see echos of the styles and thoughts between the images. Certain artists had certainly worked closely with each other or had corresponded at the very least, even commiserated over the pieces. They felt cohesive as a collection and not just random objects from a certain time or a certain place but due to their forward thinking they did not feel like relics, do not feel like they were trapped in the past. After all, this should be an art museum, not a history museum.

We took the elevator upstairs to collect our coats and leave and there, in the coat check, were 30 small children, all under the age of six. About to experience all this art. To play. As I had played through these floors, as everyone else had played through the floors. In knowing that their experience would be new and so different from mine I felt a great relief.